Working People v. The New Red Scare?

Organizing for the common good while clarifying visions of a classless society is better for us all than is the Red-baiting that tries to whip people into a frenzy over a "far left" bugbear.

In his piece for Tablet, “Labor Unions vs. Working People,” Jake Altman used the term “far left,” with and without a hyphen, a total of 17 times. He never defined it, though. Instead, he opted to cast the net of aspersions wide, ideologically ensnaring many with the political commitments, the values and the vision needed to help organize and expand a participatory labor movement that can substantially improve the lives of working people while contributing to the common good.

In this essay, I want to unpack and challenge some of what Altman wrote, while also acknowledging what I believe he got right. In so doing, I’ll try to develop an argument for what course of action I consider most conducive to creating labor unions that can help people with things “like paying rent and supporting their families,” to borrow from the “dek” in Altman’s piece. But I also believe we should be putting forward and clarifying visions of a society wherein people need not worry about those things. I’ll try to do that in part, focusing on the forms of organization I consider capable of helping us better realize what being human can mean.

Education, Media and the Common Good

In his piece for Tablet, Altman raised suspicions about unions in higher education, presumably public and otherwise. He also questioned K-12 educator unions, thereby tacitly disparaging public education at that level. (“Any national union with significant higher education membership must be wary of the extremist left,” Altman wrote, adding: “Even K-12 locals are susceptible.”) This is at a time when there’s a war on public schools that appears to be intensifying under anti-Leftist premises similar to those Altman advanced in his piece. The major casualties of that war will be families who can’t afford and/or those who would find it exceedingly difficult to access and gain entry into private educational institutions.

I’d be remiss not to note that, despite Altman’s fears of folks involved in K-12 instruction, organizing among educators at that level has been a bright spot for labor this millennium. The Chicago Teachers Union strike in 2012 brought together teachers, parents, students and the broader community in a counter-offensive against the multi-front attack on public education, on the public sector and on the unions within it. As one high school teacher who was involved in the solidarity campaign to support the CTU before and during their historic strike wrote for the unabashedly socialist Monthly Review, the CTU’s Caucus of Rank and File Educators, by forging alliances with community members and social movement organizations, transcended “traditional trade-union politics and became the inspiration for a new vision of social unionism.” Altman suggested otherwise, but if other unions want to achieve similar success and win substantive contract gains, the teacher concluded, then they’ll “have to see their struggle as one focused on building a movement to transcend their own particular demands and needs—one that aspires to fight for social justice for all. Issues like the minimum wage, racism, health care, immigration, and foreclosures need to be as important to unions as the grievance procedure.”

The CTU strike in 2012 demonstrated the importance of organizing for the common good. Six years later, teachers in the Republican-dominated state of West Virginia went on an unauthorized wildcat strike that won them a pay raise and a pledge from the governor to freeze out-of-pocket healthcare costs, demonstrating the importance of the rank and file making decisions for themselves and taking self-directed, militant coordinated action of the kind the “far left” has a history of organizing.

Yet, even if he did so clumsily and indirectly, Altman raised appropriate questions about the role of socioeconomic class in organized labor, and his piece prompts us to evaluate the role higher education has played in reproducing class society. Class antagonisms have suffused social movements, especially since the advent of the New Left in the 1960s, as Barbara and John Ehrenreich argued in their two-part essay about the professional-managerial class (PMC), published in 1977. We ignore those antagonisms at our own peril. “In fact,” the Ehrenreichs wrote, “any left ideology which fails to comprehend the PMC and its class interests, there is always a good possibility that the ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’ will turn out to be the dictatorship of the PMC.”

A generous reading of Altman’s essay might infer parallels between his critique and what the Ehrenreichs cautioned against. His concern that educational unions are exerting excessive influence over organized labor can be interpreted as evidence of astute, if also muddled, class consciousness critical of one strata dictating to those with less socioeconomic and cultural capital what their interests are and what they should do.

“But much has changed since we surveyed the American class landscape over thirty years ago,” the Ehrenreichs wrote in a 2013 essay, revisiting their analysis of the PMC from decades back. As they observed, a number of “professional jobs have been severely downgraded, as illustrated by the replacement of tenure-track professors with low-wage ‘adjuncts.’” At the same time as more women, more people of color and more people from less affluent backgrounds have been pursuing higher education, getting degrees and going to graduate school, tenure positions have disappeared and contingent, part-time and per-semester contracts for college instructors have taken their place. Many professors, a number of which come from modest backgrounds, are now “freeway fliers,” forced to cobble together classes at multiple campuses each term to barely get by. And with the cost of college doubling in the last 40 years, young people in the US are now drowning in student loan debt—$1.74 trillion worth in total.

The public good is incompatible with the not-so-covert privatization of education via ever-increasing tuition costs that price people out of a potentially edifying learning experiences and that feed a debt regime that disciplines the workforce in ways that discourage the risk-taking involved in taking collective action. It’s also incompatible with making educators into paupers too exhausted and pressed for time to refine their pedagogy because they’re compelled to take on absurd workloads or to pick up other jobs to make enough to cover rent, take care of bills and pay back student loans.

Academic workers can benefit from organizing, and they should. Their organizing can and should in turn uphold education as a common good. That can involve participating in critical pedagogical efforts that are not limited to the confines of campus. And that need not entail exercising inordinate influence or decision-making clout over others. Organizing for the common good can construct spheres for participatory knowledge production and cultural enrichment outside of academia, even as it also involves defending and endeavoring to enhance public education, be it K-12 or collegiate.

Yet, as Altman rightly intimated, higher education shouldn’t a hegemonic epicenter of organized labor. Bear in mind that, according to the US Census Bureau, less than 40 percent of folks in this country have a college degree. Those numbers no doubt reflect the conversion of higher learning into an expensive commodity not everyone can afford. Nevertheless, the greater good is antithetical to arrangements under which degrees function as a mechanism to reproduce class divisions. Higher education can and should be part of the commons without it being a part everyone is forced to engage with in order to have a good life. The credentialism associated with college degrees today is, according to Michael Sandel in “The Tyranny of Merit: What’s Become of the Common Good?,” a socially acceptable prejudice. It shouldn’t be.

Sandel, drawing on “Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism,” a New York Times bestseller by Anne Case and Angus Deaton, observed that death rates for college grads have declined 40 percent while death rates for those without a degree have increased 25 percent. Men without a bachelor’s degree in 2017 were three times more likely than those with degrees to die “deaths of despair,” the phrase Case and Deaton brought into popular parlance, referring to, as they explained, the “epidemic of deaths caused by suicides, drug overdoses, and alcoholic liver disease.” Whether or not you graduate from a four-year university should not determine whether or not you’re consigned to a premature death vis-à-vis your credentialed peers.

The state of affairs begs big questions about education and the economy. In a 2014 piece about student demonstrations for free higher education in the UK, the late anthropologist and social theorist Graeber made an apropos remark, asserting “that education doesn’t just exist for the sake of the economy,” but rather, “the economy exists to give us the means to pursue education.” That likely should be one aspect of the economy’s raison d'être, at any rate; our economic organization also ought to confer to us all the ability to co-educate ourselves. It ought to encourage rather than discourage our capacities to explore, interrogate and collectively rethink the world we create. The way we organize ourselves ought to enable us to spend time learning, thinking, deliberating, dissenting, philosophizing and collaboratively producing new knowledge. Higher education can be a space where all that occurs. It just need not be a privileged or gated space, nor the only space where liberatory co-creation and communal application of knowledge happens.

Likewise, we can endeavor to keep other institutions that should embody the public good, like journalism and media more generally, from actively reproducing class society. That’s especially true for self-proclaimed progressive outlets that in theory endeavor to advance the kind of necessary vision I alluded to before.

After an editor at Tablet politely declined to publish the rejoinder to Altman I wanted to write, I pitched one of those progressive outlets, to no avail. Understandable. Editors can only commission so much. Yet, I did notice the outlet I pitched recently published a piece about police and protest at Yale. That story headlined a recent e-newsletter the outlet distributed. The story was worth publishing, to be sure, as it documents a disturbing trend of repression not limited to elite institutions; through a public records request, the author also brought to light the methods being used to squelch dissident speech and assembly. But the publication and prioritization of an article focused on affairs at an Ivy League school exemplifies the penchant of too many Left-leaning outlets to privilege news and content about and of most interest to the affluent.

Similarly, those outlets too often hire Ivy-educated editors and staff. With fewer and fewer journalism jobs out there, working people who do not come from the upper socioeconomic strata lack the social and cultural capital that individuals from wealthier backgrounds parlay into landing coveted staff positions in newsrooms and the like. I suspect the situation is not great in terms of encouraging reporting and writing most attuned to the perspectives and struggles of people who worry about whether they will be able to make rent and pay their bills on time, to riff on Altman’s “dek” again.

Media worker organizing could make a difference. But media workers can organize to do more than help ensure it’s not just those with pricey private educational experience who fill their ranks. While the newsroom unionization wave we’ve seen in recent years offers reason for optimism, journalistic and digital-cultural labor, especially at self-identifying progressive and Left outlets, could organize around issues of ownership and control of media production. Borrowing a bit from what Michael Albert has advocated, media workers can try to democratize decision-making power and to realize workplaces, physical and virtual, wherein none are forced to be subordinate and wherein nobody monopolizes creative and empowering work.

A Closer Look at the Left and Leftist Traditions

In his piece, Altman didn’t discuss organizing much at all, save for suggesting “forces of moderation” need to organize. But those moderate “forces” have proven themselves to be pretty piss poor at grappling with and improving the tough “on-the-ground realities” that, he rightfully stressed, working people are up against.

The Democratic Party establishment which, while never a Leftist party in any meaningful way, once again distanced itself from Leftist traditions, embracing more “moderation” in the last presidential election. Granted, “moderation” in the current context means acceptance of a trillion in student debt, spending more on health care here than any other wealthy nation does with worse outcomes, incarcerating more people than any other country on the planet and ensuring none of the paid time off a plethora of other countries guarantee people. It also has meant continued support for mass slaughter—a point to which I’ll return. In this last presidential election, that purportedly moderate platform subsequently got rejected by the majority of working people who desperately wanted to, somehow, shake up the system they know is not working for them.

The estrangement of liberal politics and political figures from the Left has also meant greater alienation from traditions of effective working class organizing. The incessant emails and text messages from the Harris campaign during the election cycle illustrated the ineptitude of a mobilizing model and the absence of organizing acumen. That’s just a symptom of a deeper problem that can be examined historically, however.

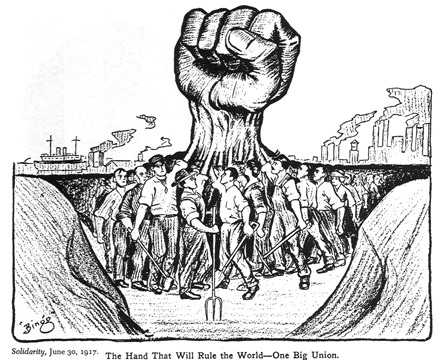

Back in the early-to-mid 20th century, the Congress of Industrial Organizations relied heavily on socialist and communist organizers when the union spearheaded sit-down strikes and won life-altering contracts for working people, as the late union organizer and labor studies scholar Jane McAlevey pointed out in “No Shortcuts: Organizing for Power in the New Gilded Age,” published in 2016. As McAlevey noted, even anti-communist labor leaders like John Lewis recognized those socialists and communists were some of the best organizers.

Although I don’t think McAlevey explored this sufficiently, those Leftist organizers also shared an interest in trying to realize socioeconomic arrangements wherein people would not have to worry about paying rent or bills. Contrary to what Altman asserts, the labor movement would benefit from advancing a vision of and a commitment to collectively crafting the sorts of widespread social relations predicated upon non-coercive mutual aid that do not reproduce alienation, exploitation or domination and that instead afford people say in the decisions that affect them. Precarious work controlled by others who reap the profits and tell you what to do ought to be viewed as a dehumanizing extreme, one at odds with participatory democracy and one that demands more than just a moderate vision and approach.

As regards his favored “forces of moderation,” Altman praised the “anti-communist coalitions of the 1940s and 1950s,” i.e., networks of reactionary activists under the sway of McCarthyism who helped decimate organized labor. Those esteemed “forces of moderation” purged people on the Left—that is, they forced out the best organizers—from unions like the CIO. As one labor historian put it, the “most dedicated and visionary unionists” were excommunicated.

Altman decried failed “liberal politics,” but his rhetoric parallels the faux progressive politics Phil Ochs satirized some time ago in his tongue-in-cheek track, “Love Me, I’m a Liberal”: “I cheered when Humphrey was chosen / My faith in the system restored / I'm glad that the Commies were thrown out / Of the A.F.L. C.I.O. board / And I love Puerto Ricans and Negros / As long as they don't move next door / So love me, love me, love me, I'm a liberal.”

Moreover, the anti-communists Altman extolled attacked the rank-and-file led, class struggle-oriented unions like the UE and the ILWU. Those “forces of moderation” dished the business class a major assist by helping to drive a wedge between the civil rights movement and the organizing for economic justice they painted and vilified as Red.

Altman’s piece reiterates Red-baiting rhetoric that has historically been used against organized labor. Peddling an anti-Leftist bugbear reinforces a worldview that will never adequately serve working people.

Solidarity for a Freer Humanity

In addition, Altman framed his essay in a way that further obscures values and commitments found in Leftist traditions, while further legitimating right-wing efforts to undermine public higher education as a common good—or as what could and ought to be a common good capable of enriching our lives in a decent society.

He derided "often-troubled [college] campuses where trashing the whole of American history as an 'imperial project' and promoting pro-Hamas propaganda to demonize the State of Israel are paramount values." Ironically, his framing chides nuance-lacking criticism while abandoning nuance to ideologically elide and justify documented state terror.

Starting with US history and Altman’s use of scare quotes to invoke a label (“imperial project”) he, I gather, considers inappropriate, it is worth recalling the explicit aims of our country’s founding figures. The oft-cited foreign policy critic Noam Chomsky gave a talk on “modern-day American imperialism” in which he recapped those relevant intentions.

“According to the founding fathers, when the country was founded it was an ‘infant empire.’ That’s George Washington,” Chomsky remarked in that 2008 talk. “Modern-day American imperialism is just a later phase of a process that has continued from the very first moment without a break, going in a very steady line. So, we are looking at one phase in a process that was initiated when the country was founded and has never changed.”

If we stick with a standard definition and take the term “imperial” in this context to refer to the extension of state power and influence over other territories, often accomplished through the threat and use of violence, then following the “steady line” Chomsky spoke of in relation to the record of US aggression certainly suggests an ongoing project of that sort. From a war of conquest in the mid-nineteenth century after which the US acquired land previously controlled by Mexico, to the CIA orchestrating the overthrow of the elected, Left-leaning Jacobo Árbenz government in Guatemala in the mid-20th century, to the US support for the overthrow of the democratically elected socialist administration of Salvador Allende in Chile in 1973, to the invasion of Iraq in 2003 that the then-UN Secretary General deemed illegal under international law, the historical record remains, even if Altman would rather not label (or acknowledge) it.

That’s not to suggest all of US history has been imperialist, however. That is, if we understand US history to include organizing and agitating for a classless world, then there’s more to recover. Altman wasn’t wrong to indirectly interrogate the failure of educational spaces to adequately engage with the oft-ignored record of organizing and resisting.

August Spies, an anarchist-socialist who was posthumously pardoned after being hanged in Illinois for his political commitments after a bomb was thrown at a demonstration in Chicago’s Haymarket Square in 1886, gave a speech in court that captures the thrust of that history-making from below.

But, if you think that by hanging us you can stamp out the labor movement—the movement from which the downtrodden millions, the millions who toil and live in want and misery, the wage slaves, expect salvation—if this is your opinion, then hang us! Here you will tread upon a spark, but here, and there, and behind you, and in front of you, and everywhere, flames will blaze up. It is a subterranean fire. You cannot put it out. The ground is on fire upon which you stand.

He then suggested “what you try to grasp is nothing but the deceptive reflex of the stings of your bad conscience.”

As if responding to Altman’s nightmarish conception of the “far left,” Spies continued:

You want to ‘stamp out the conspirators’—the ‘agitators?’ Ah, stamp out every factory lord who has grown wealthy upon the unpaid labor of his [employees]. Stamp out every landlord who has amassed fortunes from the rent of overburdened workingmen and farmers. Stamp out every machine that is revolutionizing industry and agriculture, that intensifies the production, ruins the producer, that increases the national wealth, while the creator of all these things stands amidst them tantalized with hunger! Stamp out the railroads, the telegraph, the telephone, steam and yourselves—for everything breathes the revolutionary spirit.

Point being, US history is not only imperialist if it includes the history of those in the US, like Spies and his fellow Haymarket martyrs, who dared challenge the “forces of moderation” Altman valorized.

And as Chomsky also observed, we’re not so unique here in the US; others capable of wielding large-scale violence have historically done so the way those in positions of power have repeatedly done via the US nation-state.

As for the US-backed state power, Israel, which Altman suggested those on college campuses are keen to “demonize,” we can consider the relevant facts his framing failed to include. The UN recognizes Israel as an occupying power in the West Bank, and in Gaza, where, according to the UN Agency for Palestinian refugees (UNRWA), more than 14,000 children have been killed since the Israel-Hamas war started in October 2023; a kid is killed in Gaza every hour. “Killing children cannot be justified,” UNRWA added.

And the US isn’t the only state to be critically assayed by the International Court of Justice. Last January, the ICJ concluded “Israel must take all measures within its power to prevent and punish the direct and public incitement to commit genocide in relation to members of the Palestinian group in the Gaza Strip,” and “that Israel must take immediate and effective measures to enable the provision of urgently needed basic services and humanitarian assistance to address the adverse conditions of life faced by Palestinians in the Gaza Strip.”

More recently, the international non-governmental organization Human Rights Watch released a report that found “Israeli authorities’ deprivation of water to the population of Gaza is a violation of the right to water and sanitation under international human rights law.” Israeli efforts to cut off or restrict Gazan’s access to water and other life essentials “persisted after the ICJ ruling in January 2024,” the HRW report stated. Creating conditions in Gaza intended to bring about the destruction of the Palestinian population, “inflicted as part of a mass killing of Palestinian civilians in Gaza,” per the HRW report, “means Israeli authorities have committed the crime against humanity of extermination, which is ongoing. This policy also amounts to an ‘act of genocide’ under the Genocide Convention of 1948.”

Another non-governmental organization concerned with human rights, Amnesty International, recently came to the same conclusion. Additionally, Amnesty’s report pointed to states, like the US, that aid and abet the destruction by supplying Israel with weapons. The continued sale and shipment of arms from the US in support of ongoing state terror is one reason why a number of labor unions in this country called for a ceasefire. Another reason might be that some take seriously the ethic of solidarity that has long been the bulwark of working class and Leftist traditions. Organizing and relating to each other in ways that foster a commitment to supporting and caring for the well-being of other humans is what can really make a difference in the lives of people everywhere.

In contrast, waxing critical about alleged tendencies on campuses to “demonize the State of Israel” directs the focus away from the wealth of corroborated evidence and multiple proclamations from various international organizations that strongly suggest the state continues to take actions to extirpate a population, leaving a lot of dead children, unnecessary suffering and pain in its wake, thanks in no small part to arms and political cover from the US political class.

Altman’s framing omits mutual concern as regards the above. It removes not only salient realities but also the possibility of a politics of uplift of the other—a politics that, as Graeber pointed out, has long been associated with, if also used to exploit, working people. The politics Graeber described not only can and often does resonate with workers; it’s also capable of moving us in the direction of a classless society.

Organizing in/against Class Society

Altman wasn’t wrong to address the kind of politics and classism that irks those who live paycheck to paycheck. His analysis identified pressing issues but also missed the mark. Somewhat understandably, he criticized the “DEI bureaucracy,” which can, indeed, give the well-heeled authority to police language while enforcing faux equity within an increasingly class and race stratified society.

Catherine Liu, author of “Virtue Hoarders: The Case Against the Professional Managerial Class,” has suggested Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) training in universities can cultivate an “I want to speak to your manager” attitude, which in turn empowers an administrative bureaucratic class to mete out discipline. That paternalism comes at the expense of collective agency, organizing and efforts to strengthen the bonds of solidarity capable of more meaningfully addressing the source of the problems too many DEI initiatives are only able to treat superficially.

I think the issue is less about DEI itself, though, and more about the predominantly upper-tier of the PMC overseeing those initiatives. An ethic of solidarity appears conspicuously absent, as does a critique of bureaucracy and how it enables social stratification. “Solidarity is largely a value among working class people, or among the otherwise marginalized or oppressed,” Graeber wrote in an essay published in 2017. “Professional-managerials tend towards radical individualism, and for them, left politics becomes largely a matter of puritanical one-upmanship (‘check your privilege!’), with the sense of responsibility to others largely displaced onto responsibility to abstractions, forms, processes, and institutions.” That displacement of responsibility onto a bureaucratic power structure can make even well-intentioned initiatives self-defeating. While those who denigrate the Left love to talk about the importance of personal responsibility, they seldom stress the anti-bureaucratic working-class ethos of assuming some responsibility for other individuals, buttressed by the expectation others do the same for you.

And to my knowledge, few if any DEI initiatives have addressed, say, the under-reported racial disparities in injuries and deaths on the job. Those are, quite literally, life-or-death concerns for workers that Altman, who threw shade on “identity politics” throughout his piece, opted not to concern himself with. They’re realities that an ethic of solidarity cannot abide and that ought to motivate us to organize for (interrelated) racial and economic justice.

Insofar as it elicits the desired effect, efforts to disparage the “far left” can lead to knee-jerk rejection of values and visions associated with Leftist traditions and with working class communities already heavily co-opted and hollowed out. In contrast, education, formally and informally, as a common good, should confer the ability and space to compare, contrast, unpack and reflect on what we value and what forms of social organization best engender those values.

I believe the yearning for a classless society that various parts of the Left have historically stoked reflects an oft-suppressed need for a freer humanity, one liberated from a situation in which many cannot sleep at night, beset by thoughts of losing their homes and getting evicted. If Graeber was right to suggest that the structural violence of class society perpetuates what he once termed “dead zones” of the human imagination that, I tend to think, contain our under-realized potentials.

That’s why I maintain any would-be labor or social movement aimed at improving the lives of working people probably ought to consciously try to approximate classless relations among those involved while simultaneously struggling to create classlessness on a societal scale. Participating in the partial knowledge of what it’s like to be free together can inform our understanding of how we might all live more fully free. Practicing relations that mitigate the influence of class stratification can entail democratizing decision-making power, trying to make sure nobody routinely tells others what to do or how to do it, creating conditions (albeit liminal and limited) in which everyone can regularly exercise both creativity and agency, constructing a co-culture in which no one is compelled to merely follow leaders, and nurturing the collaborative and (co-)organizing abilities of all involved.

Like many unions and even many of the organizers she extolled, McAlevey, the aforementioned labor scholar, did not adequately embrace what I described just above. Following the old CIO organizing strategy, she stressed the importance of leadership identification in her book “No Shortcuts,” and she more or less repudiated the practice of actively creating power relations of parity within a union or organizing drive. She viewed that focus as a distraction that does a disservice to organized labor. While she championed democratic unions responsive to the rank and file, I think her ideas about effective organizing and about what relations are worth creating lacked both a more thoroughgoing critique of socioeconomic class and a more robust valuation of a possible humanity characterized by cooperative coordination within caring community.

I mentioned Graeber above, and he as well as the anarchist-socialist tradition more generally made strides in putting that sort of vision into theory and practice. What Graeber called “everyday communism,” i.e. “the foundation of all human sociality anywhere,” rooted in the collaborative ways of doing and relating that we all partake in, to greater or lesser degrees, is the much-needed antidote to the class rule that characterizes existing society. It’s also what can challenge the more opaque class domination that crops up in and stymies the ability of organizing to achieve more for us all. Greater attention to and embrace of “everyday communism” within organizing efforts and aims could also help distinguish the Left, including the “far left,” from a politics that fail working people.

I think this gets at the crux of my disagreement with and criticism of what Altman wrote. He conflated Leftism with authoritarian vanguardism and classism. In so doing, his essay feeds into the new Red Scare. It fuels the fearmongering about “enemies from within,” which encourages people to associate the Left with a scourge in need of excising, thereby dissuading the critique of class rule that Leftist (and anarchist) traditions have historically advanced. Distinct goals and political practices that need to be parsed out instead get collapsed into a single signifier that ominously floats above or looms over us, clouding our political vision.

The Power of Class Struggle for Classlessness

The “far left” bogeyman Altman bemoaned is, according to him, “organized through Labor Notes and the Democratic Socialists of America, an organization filled with and now governed by Leninists. They are aggressive and hungry for power. Power means jobs.” First, we’ll set aside the lack of evidence for the assertion and for the association of Labor Notes and DSA with the “far left,” which Altman seems to disparage but again never defines. Second, it’s worth noting the DSA has an active libertarian socialist caucus antithetical to anti-democratic Leninism. Third, writers affiliated with the “far left” Labor Notes crew had the audacity to suggest, in their “Secrets of a Successful Organizer” text, that anyone can learn and apply the basics of organizing. Only those hungry for power would put forward such an egalitarian idea, clearly.

Aside from equating power with jobs without any additional explanation, Altman didn’t explore the concept of power in his piece. I’ll briefly do that here so as to add useful perspective.

Many people who have been stripped of socioeconomic power and denied agency on the job where they have little-to-no say in decisions affecting them and where they find themselves precariously employed and/or incessantly monitored, controlled, forced to work faster without sufficient breaks and paid too little to live decent lives are, rightfully, hungry for power. I think it’s safe to say many want jobs that afford dignity that existing power relations too often fail to provide. Many want to know if they’ll have income needed to pay rent and bills six months down the line; power inequities today render that uncertain. Many want sufficient remuneration needed to live with a modicum of joy and comfort, which entrenched economic hierarchies make it harder to acquire. Many might appreciate and benefit from having input in workplace decisions, which many won’t have unless collective action with fellow workers transforms dominant power dynamics.

A key organizing aim ought to be to democratize economic and worksite power so that the owners and managers who are otherwise institutionally incentivized to mistreat, micro-manage, poorly compensate and super-exploit workers cannot unilaterally make decisions or take actions that enable them to continue doing that.

As the Labor Notes-affiliated authors of that “Secrets of a Successful Organizer” text pointed out, one commonly accepted tenet of effective organizing entails assisting co-workers in realizing who has the power to implement desired changes where they labor. “In any workplace,” they wrote, “the underlying issue is power: who has it, who wants it, and how it’s used.” But, they added, “many people are uncomfortable with power. They find it hard to talk about, and are reluctant to seek it. People shy away from the conflict and unpleasantness it implies.”

What Altman wrote elides the existing imbalances that have to be addressed if labor organizing is to be effective, even on his terms. That’s because typical corporate arrangements concentrate influence and the ability to command among a select few—namely shareholders, owners and managers. The “Secrets of a Successful Organizer” authors emphasized speaking with and listening to fellow workers to build relationships based on trust that are needed for collective action, like a march on the boss or a work stoppage. That collective action, an exercise of shared power, is what’s required to pressure those with the preponderance of power over labor to use their agglomerated authority to improve wages, working conditions and the like.

Class struggle for power is necessary but insufficient. Without it, the institutionalized power disparities remain intact, and those disparities will remain synonymous with class society, along with the surfeit of suffering associated with it. But class struggle can also be organized in such a way, and with the collective intent, of recasting social relations so that no individuals or groups of people would be able to exercise undue power over others—not the ruling class, not the PMC, not an educated intelligentsia, and not the “far let” Altman’s essay entreats readers to disdain.

Permit me to break it down: A labor campaign intended to improve working people’s lives will benefit from taking into account and trying to change existing workplace power relations. Those power relations are rooted and manifest in ownership structures, in the servile roles for workers and in the absence of organized labor that could meaningfully influence the given arrangements. That ambitious labor campaign can likewise benefit from efforts to address concentrations of wealth and economic power writ large. To make the most meaningful gains, organizers and movement makers can intentionally seek to displace institutions that function to keep working people subjugated and in constant fear of how they will support their families and pay bills. To do that most effectively and profoundly, I think, requires hunger not for exercising power over others, per se, but instead a hunger to undermine the routinized practices of some wielding power over others, along with a thirst for better norms regarding how we empower each other and exercise the naturally endowed, untapped powers (I’m inclined to believe) humanity as a whole, deep down, desires to make manifest.

So I want to suggest there’s value to be realized by organizing for relations characterized by solidarity-oriented mutual empowerment, for arrangements that ensure no person or class amasses the ability to force or coerce others. And insofar as that value is inextricably linked to the methods for bringing it into being, then I want to suggest there is also immense value in approaches to and forms of organizing that epitomize, to the extent possible, the care and freedom of the classless interpersonal relations the organizing is intended to normalize. The same holds true, I think, for the structures and vehicles, like labor unions and social movements, that we use to advance organizing aims; they too can embody the ways of relating to and acting in concert with one another capable of emancipating us from the conditions of estrangement that reproduce painfully crippling iterations of humanity. I don’t think we’ll know just how under-empowered we all are, as a species and as individuals within the species, until we gain greater experience with thinking, behaving, living and co-organizing, if only partially at first, in ways that liberate our impoverished sense of self, of society and of what we’re capable of being.